Enough fossil fuels in schools

The Western Australian government announced last week that Woodside Energy would give $7 million over five years to support public schools in the Pilbara region, where the company operates its Burrup Hub gas facilities. For years, Woodside has been funding Karratha Senior High School and Roebourne District High School, as well as the Catholic school St Luke's College. Now, it will expand its Karratha and Roebourne Education Initiative to include seven primary schools in the area. Education Minister Tony Buti said he was "thrilled this partnership between Woodside Energy and the Department of Education will continue for years to come".

It's reasonable to expect some of the billions made from extracting Australia’s natural resources to provide for public services like education. The obvious way for that to happen is through taxation, but our big polluters get away with paying little, and our politicians settle for morsels like Woodside's school funding package. Australia could take a lesson from Norway, where oil and gas companies are taxed at around 78%. That way, primary school students could receive the education they deserve without being reduced to PR fodder.

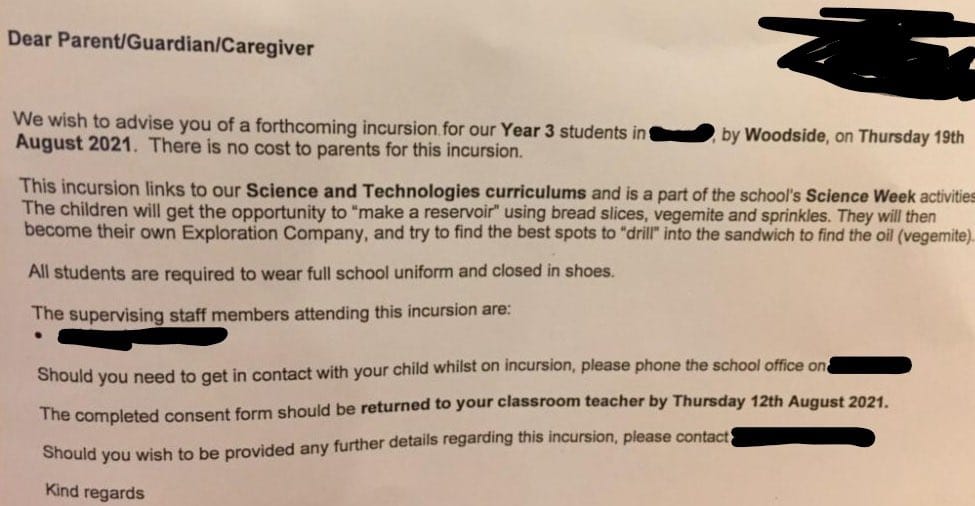

Woodside has form when it comes to education: In 2021, parents were disturbed when Woodside visited schools and used Vegemite and fairy bread to teach primary students how petrochemical extraction works. The company sponsors the FutureLab innovation program at the University of Western Australia and has its name on the Woodside Building for Technology and Design at Monash University. Generations' worth of Western Australian school excursions have visited the SciTech museum in Perth, which is sponsored by both Woodside and Chevron.

A few years ago, when I taught English at a Perth public high school, I discovered another way fossil fuel companies spread their insidious influence: careers education. Every so often, a whole class of my students would enter their lesson carrying blue water bottles emblazoned with the Chevron logo. I knew it meant they'd been at a careers assembly where representatives of the multinational had spruiked jobs in oil and gas. Students would tell me there'd been no mention of the fact that fossil fuel expansion was inconsistent with the world having any chance of meeting its climate targets. I was glad to have never been rostered on to supervise one of these careers sessions. I don't think I could have held myself back from staging an intervention.

The vast majority of schools in Western Australia teach the federal Education Department's Australian Curriculum, which contains three 'Cross-Curriculum Priorities' intended to be embedded in all learning areas. One of these priorities is Sustainability. Students are supposed to learn about it in all of their subjects, with a focus on how people can take collective and individual action to ensure "fairness across generations into the future." The WA government has committed to a curriculum that supposedly has environmentalist values at its core.

The nature of a standardised curriculum is that it turns education into a box-ticking exercise: Knowledge and skills become a list of points to be checked off as quickly as possible so they can all fit into a term's programming. In my time teaching, this felt especially true of Sustainability and the other Cross-Curriculum Priorities, which teachers had to cram into already crowded lessons. In English, read a poem about a tree: Tick. In maths, have students solve a problem about quantities of recycling material: Tick. In PE, call the teams in your round-robin dodgeball tournament Earth, Fire, Wind, Water, and Heart: Tick. A truly ecological education would require something more: a fundamental rethink of what schools are and what they're for. An obvious starting point would be that they're not sponsorship opportunities for inherently unsustainable industries. It's hard to take a sustainability curriculum seriously when it has a Woodside logo slapped on it.

Everything Woodside does is to fulfil its obligation to maximise shareholder profit. It invests money in education not out of kindness, but to exert cultural influence so it can appear like a natural, necessary, and benevolent force in Western Australian life. When fossil fuel companies embed themselves in arts and cultural institutions, it's disturbing enough, but there's something particularly perverse about their burrowing into schools. Huge numbers of young people are made depressed and anxious by the climate crisis. Woodside is destabilising the very future its educational programs are supposed to prepare students for.

Member discussion